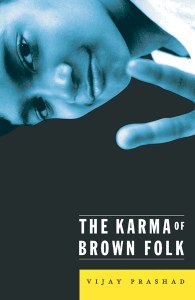

The Karma of Brown Folk

Vijay Prashad

In this kaleidoscopic critique, Prashad looks into the complexities faced by the members of a “model minority”-one, he claims, that is consistently deployed as "a weapon in the war against black America."

For any of us who have agonized over our identities as South Asians in America, The Karma of Brown Folk is must reading. It is thoughtful, thoroughly researched, well written, and above all, provocative. Prashad pulls no punches. He has set the standard by which future works on the Asian diaspora must be judged.

Abraham Verghese, author of The Tennis Partner and My Own Country

“How does it feel to be a problem?” asked W. E. B. Du Bois of black Americans in his classic The Souls of Black Folk. A hundred years later, Vijay Prashad asks South Asians “How does it feel to be a solution?” In this kaleidoscopic critique, Prashad looks into the complexities faced by the members of a “model minority”-one, he claims, that is consistently deployed as "a weapon in the war against black America."

On a vast canvas, The Karma of Brown Folk attacks the two pillars of the “model minority” image, that South Asians are both inherently successful and pliant, and analyzes the ways in which U.S. immigration policy and American Orientalism have perpetuated these stereotypes. Prashad uses irony, humor, razor-sharp criticism, personal reflections, and historical research to challenge the arguments made by Dinesh D’Souza, who heralds South Asian success in the U.S., and to question the quiet accommodation to racism made by many South Asians. A look at Deepak Chopra and others whom Prashad terms “Godmen” shows us how some South Asians exploit the stereotype of inherent spirituality, much to the chagrin of other South Asians. Following the long engagement of American culture with South Asia, Prashad traces India’s effect on thinkers like Cotton Mather and Henry David Thoreau, Ravi Shankar’s influence on John Coltrane, and such essential issues as race versus caste and the connection between antiracism activism and anticolonial resistance.

The Karma of Brown Folk locates the birth of the “model minority” myth, placing it firmly in the context of reaction to the struggle for Black Liberation. Prashad reclaims the long history of black and South Asian solidarity, discussing joint struggles in the U.S., the Caribbean, South Africa, and elsewhere, and exposes how these powerful moments of alliance faded from historical memory and were replaced by Indian support for antiblack racism. Ultimately, Prashad writes not just about South Asians in America but about America itself, in the tradition of Tocqueville, Du Bois, Richard Wright, and others. He explores the place of collective struggle and multiracial alliances in the transformation of self and community-in short, how Americans define themselves.

Awards

Village Voice Favorite Books of 2000

$19.50 paper ISBN 978-0-8166-3439-2

$57.00 cloth/jacket ISBN 978-0-8166-3438-5

272 pages, 21 b&w plates, 5 7/8 x 9, 2001

Vijay Prashad is associate professor and director of international studies at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut.

For any of us who have agonized over our identities as South Asians in America, The Karma of Brown Folk is must reading. It is thoughtful, thoroughly researched, well written, and above all, provocative. Prashad pulls no punches. He has set the standard by which future works on the Asian diaspora must be judged.

Abraham Verghese, author of The Tennis Partner and My Own Country

The Karma of Brown Folk is one of the most stunning, wide-ranging, powerful books I've read in years. Prashad is truly heir to Du Bois, for his prose just rises off the page; it is full of irony and humor and yet offers razor sharp criticism, personal reflections, historical research, and analytical focus. I love this book. It is readable and lively, it embraces the poetic spirit and takes a political stance.

Robin D. G. Kelley, author of Yo' Mama's Disfunktional! Fighting the Culture Wars in Urban America

Vijay Prashad ponders the rise of Asian America-and calls for ‘model minority suicide’-in this smart, biting rumination on color lines in multiracial America. Along the way, he produces a complex picture of emergent South Asian communities. Indeed, The Karma of Brown Folk is both a fascinating genealogy of America’s idea of India and a love/hate letter to Prashad's fellow desis, or South Asian immigrants. At the heart of the book is Prashad's history of the model minority myth, which he traces to Cold War immigration reforms and civil rights movement backlash. The myth offers Asians the role of ‘perpetual solution to what is seen as the crisis of black America,’ and riffing on Du Bois, Prashad suggests the question for Asian Americans is: ‘How does it feel to be a solution?’ A kaleidoscopic critique that deconstructs the logic of Asian American chauvinists like Dinesh D'Souza as well as the ‘New Age Orientalism’ of Deepak Chopra, The Karma of Brown Folk is remarkable not only for its radical analysis of U.S. racism but of desi ‘bad faith’-even as it contains fascinating accounts of Afro-Asian collaboration and multiracial organizing.

Village Voice

Intellectually feisty and wry, Prashad describes various American misunderstandings of India, cherished as much by Emerson as by Walt Disney: the often quite harmless, when not interesting, exaggerations and omissions that the easy pejorative ‘Orientalism’ swallows up these days. Prashad’s considerable book is part of a clear-sighted assessment of a fast-changing people and world.

Times Literary Supplement

Prashad begins by tracing the evolution of an American strain of Orientalism in the early 19th century. He demonstrates how this method of cultural reification was transmitted through popular culture, such as brown-face shows in circuses that toured the country. This Orientalism, according to Prashad, finds its way into the modern day with ‘sly babas and Godmen’ like Deepak Chopra who exploit its East/spiritual-West/material dichotomy for their own personal profit. He then shifts gears, addressing a range of topics including immigration policies, the difficulties of building ‘authentic cultural lives’ in America, the often Hindu-nationalist, political underpinnings of nonpolitical cultural organizations in the immigrant community, and finally, the sources of and possible solutions to South Asian anti-black racism. The Karma of Brown Folk is fascinating reading because of the very ‘experiential’ knowledge that the author explicitly wishes to submit to more ‘theoretical’ bases of understanding. He is a keen eye-witness of South Asian American (desi) life in America, especially when interpolating snatches of conversation or reporting events. He has a genius for selecting the precise detail that makes observations spring to life. For example, Ralph Waldo Emerson’s pet name for his wife was ‘Mine Asia,’ and Dizzy Gillespie sometimes wore a turban to pose as South Asian in order to escape the restrictions of American apartheid.

A. Magazine: Inside Asian America

Prashad’s book is a sharp, often witty attack on fellow Indians, who, knowingly or unknowingly, ally with the whites against African Americans and other disadvantaged minorities. Readable and thought-provoking.

India Today International

The Karma of Brown Folk is remarkable not only for its radical analysis of U.S. racism but of desi ‘bad faith.’ Prashad deconstructs the logic of Asian American chauvinists like D’Souza, as well as the ‘New Age Orientalism’ of Deepak Chopra. He provides an extended meditation on the paradoxes of ‘reverse assimilation,’ in which all too often young desis counter persistent racism with a static, fetishised version of ‘homeland’ culture. Most instructively, in a sharp analysis of the rise of what he calls Yankee Hindutva, Prashad offers an object lesson in how Asian American community-building-in this case U.S. cultural outposts of India’s Hindu Right-can also build American racism: ‘Rather than join what should be a collective battle to reconstruct society along the lines of compassion and fellowship, Yankee Hindutva asks desi children to withdraw into Hindu enclaves to learn the ways they are greater than others.’

Village Voice

Taking a cue from W. E. B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk-which poses the question, ‘How does it feel to be a problem?’-Prashad’s book on race relations asks Asians, ‘How does it feel to be a solution?’ He shows us how neoconservatives have used the success of South Asian immigrants to argue that America now offers a level playing field and that if other minorities, particularly African-Americans, have not achieved as much success, it is due to their own lack of initiative. Yet Prashad demonstrates how the U.S.’s extremely selective immigration policy (from 1966 to 1977, for example, 83% of Indian immigrants to the U.S. were professionals) has led to the myth of the ‘successful race.’ In the same vein, Prashad also argues that ‘sly Babas’ (or ‘Godmen’), like Deepak Chopra, perpetuate the idea that Asians are a pliant, spiritual group and do a disservice by peddling ‘opiates of comfort’ rather than challenging people to alter the causes of their distress. Prashad includes many revealing insights about South Asian in America.

Publishers Weekly

Vijay Prashad’s book The Karma of Brown Folk is a protest against what might be called offshore nationalism. Very few books written in the West by Indian scholars living here have conveyed the level of political energy and exuberance that The Karma of Brown Folk does. I do not know of any other book of its kind that is as generous in noting the labor of desis. Nor have I read another book that is a hopeful.

Amitava Kumar, Little India

A welcome breeze from the overheated rhetoric of some of the post-colonial literature. Defying genres, and using scholarship at service of a much-needed polemic, Prashad serves up a heady brew.

Chicago South Asia Newsletter

This book is well documented and biting, if not bitter, in its assessment of a narrow aspect of the lives of a newer immigrant group to the United States.

MultiCultural Review

The Karma of Brown Folk is arguably a bold foray in dismantling the stereotypes about the Indian subcontinent and South Asians in general. The aura of an inherent Eastern spirituality, the unexplored flexibility of accommodation to the ideals of white supremacy, is replaced with an argument for the start correlations between Western racism and the Indian caste system, and between Civil Rights activism and anti-colonial resistance. I highly recommend this book for believers in justice for all.

Amy Dadichandji Laly, Pacific Reader