MN State Fair Feature: Crop art and corn carnivals

Crop Art and Cereal Architecture

If the crop-art exhibit is one of your MN State Fair must-sees, here's a little background on how the whole art form was established—along with some lesser-known background on the Midwest's earliest fairs. (Excerpt from Corn Palaces and Butter Queens: A History of Crop Art and Dairy Sculpture by Pamela H. Simpson.)

If the crop-art exhibit is one of your MN State Fair must-sees, here's a little background on how the whole art form was established—along with some lesser-known background on the Midwest's earliest fairs. (Excerpt from Corn Palaces and Butter Queens: A History of Crop Art and Dairy Sculpture by Pamela H. Simpson.)

Note: Hover over any images here, and their captions will display.

HENRY WORRALL: CROP-ART PIONEER

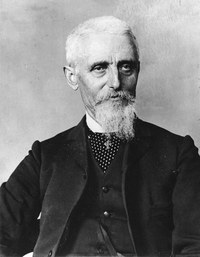

Henry Worrall (1825–1902) was ten when he and his father immigrated to the United States from England. Settling in Cincinnati, the younger Worrall eventually became an accomplished musician, composer, and teacher. In 1868, he and his wife moved to Topeka, Kansas, where, within the year, he was not only teaching music but also painting oil portraits of local leaders. Over the next few decades, his drawings for publications such as Frank Leslie’s Weekly would earn him a considerable reputation as an illustrator.

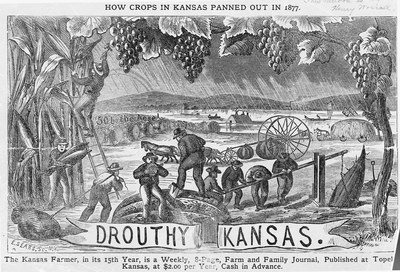

Worrall’s best-known drawing, however, was one he did as a joke, in 1869. Kansas had suffered a terrible drought in 1860, but ample rains in the next decade brought full recovery. Still, rumors persisted of a drought-ridden region, and his old friends in Cincinnati teased him about the awful place he had moved to. When a group of them visited in 1869, Worrall (pictured at left) prepared a large charcoal drawing he called Drouthy Kansas, set it up on an easel in his studio, and had a local photographer make small photo-card copies of it to give his friends as souvenirs. Drouthy Kansas depicted a place where men had to use ladders and hatchets to cut corn from huge stalks, derricks to lift yams, and ropes to pull boulder-size potatoes. A sign proclaimed “50 [bushels] to the acre” over a wheat field while rain poured into a flooding river.

Worrall’s best-known drawing, however, was one he did as a joke, in 1869. Kansas had suffered a terrible drought in 1860, but ample rains in the next decade brought full recovery. Still, rumors persisted of a drought-ridden region, and his old friends in Cincinnati teased him about the awful place he had moved to. When a group of them visited in 1869, Worrall (pictured at left) prepared a large charcoal drawing he called Drouthy Kansas, set it up on an easel in his studio, and had a local photographer make small photo-card copies of it to give his friends as souvenirs. Drouthy Kansas depicted a place where men had to use ladders and hatchets to cut corn from huge stalks, derricks to lift yams, and ropes to pull boulder-size potatoes. A sign proclaimed “50 [bushels] to the acre” over a wheat field while rain poured into a flooding river.

Echoing the American folk tradition of the tall tale, the image was a great hit not only with Worrall’s friends but with others as well—it made Worrall famous. The photographer had steady sales of his cards; the image was engraved for the cover of the Kansas Farmer in 1879 and then reproduced on both an official state handbook meant to attract settlers and one put out by the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad. It even appeared on a painted drop curtain for a theater in Lawrence. Worrall exhibited the original charcoal drawing at the State Agricultural Society in 1870 and later made a copy of it in oil that survives in the Kansas State Historical Society’s collection. Period commentators claimed the illustration was “the best advertisement for Kansas that was ever published.” When Kansas had another drought and grasshopper infestation in 1874, Worrall reported that farmers wrote him and even accosted him on the street complaining that it was his Drouthy Kansas picture that had seduced them into settling in the state and had caused their ruin.

When good rains and harvests in 1875 and 1876 again brought prosperity, Kansas was eager to dispel the myth of barren farms. State officials may have been thinking about Drouthy Kansas when they offered Worrall the chance to make his two-dimensional image a three-dimensional reality at the Centennial Exposition, or they may have been impressed by the crop art he had been supplying to the Kansas State Fairs since 1872. Worrall’s fruit pyramids, apple pagodas, and festoons of grains were modest compared to what he would later make for Philadelphia, but they reveal that he was familiar with the art form and that artful displays of produce were something state officials hired artists to create.

Still, there was nothing at any fair that matched the scale of Worrall’s centennial exhibit in Philadelphia. The goal, like that of Drouthy Kansas, was to create a visual iconography that expressed the idea of a Kansas so fertile and so extraordinarily blessed with natural resources that the viewer could imagine this was Cockaigne, the legendary land of plenty.

Because Kansas officials thought that the space allotted the states in the exhibition’s main buildings was too limited, they joined with Colorado’s organizers to erect the largest state structure on the grounds. Colorado occupied the west wing of the Greek cross–shaped building, and the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad had the east wing. Kansas took up the central axis. Responsible for decorating both the railroad and the Kansas portions, Worrall diligently collected crops from all over the state, shipped them to

Philadelphia, and covered the walls with stalks of corn, filled glass columns with oats and rye, and constructed Corinthian capitals out of grain heads. In the center of the rotunda, he hung a crop-art version of the Liberty Bell. More than 8' high, the bell was fashioned of broomcorn, millet, and wheat; the clapper was a huge gourd. On the back wall, sunburst rays of cotton and corn surrounded grain-art versions of the state seal and a map of the Kansas counties. In the fall, Worrall closed the exhibit for two days and astounded everyone by reopening with a new feature—a model of the U.S. Capitol, 20' high and covered with apples. No other state had troubled even to renew its exhibits with fresh produce; Worrall had created a whole new display.

Reporting on the exhibit, the Kansas Board of Agriculture claimed, “Our success in the inter-state contests heretofore, has arisen from a genius for arrangement and ornamentation, as well as from the merit of our products.” The board was right—it was both the merit of the fruits and grains and their artistic arrangement that had drawn so much attention. The purpose was to “group and blend the products of nature and art for scenic effects” in order to “excite universal comment and make the Kansas Headquarters a place to be sought and admired.” Worrall clearly succeeded; nearly every commentator on the Centennial Exposition seemed to mention the special character of the Kansas display.

Worrall did not invent crop art, but there were few contemporary precedents for what he created in Philadelphia. The 1851 London Crystal Palace’s tins of meat and champagne bottles stacked in pyramids and the 1853 New York Crystal Palace’s sugar-paste model of Greenwich Village were single exhibits, not the integrated whole that Worrall designed for the Centennial Exposition. Wherever he got the idea—from European harvest festivals or seventeenth-century Cockaigne arches, from Renaissance banquet centerpieces, rustic folk art, or state-fair fruit pyramids—Henry Worrall became one of the chief nineteenth-century practitioners of the art.

***

MIDWESTERN CROP FESTIVALS

In 1895, as E. W. Howe, the founder of The Atchison (Kansas) Globe, was thinking about the popularity of Sioux City’s and Mitchell’s Corn Palaces, as well as the crop-art displays at the Chicago Columbian Exposition, an idea occurred to him. “Why couldn’t Atchison have a Corn Carnival?” He asked that question in an editorial note and went on to suggest that a “dozen things could be done to amuse visitors during the day, and at night we could have a carnival on the streets, and blow horns and wear masquerade costumes, and rejoice like the Indians do over a big corn crop.” He concluded with a call to arms: “Who will jump in and work it up?”

With Howe’s leadership, many people were willing to help. Atchison, a town in northeastern Kansas that then had a population of a little more than fifteen thousand, would eventually hold seven Corn Carnivals between 1895 and 1912. Usually multiday events, the celebrations attracted huge crowds for parades, bands, baseball games, vaudeville performances, fireworks, and balloon ascents. The 1899 event, for example, drew a crowd of twenty-five thousand to see fourteen bands and nearly one thousand entries in the parade. There was a decided sense of fun to the carnival. Dressed up in corn costumes, the populace was invited to pelt each other with corn kernels. Atchison merchants filled their store windows with displays of corn art, and the regional railroad companies sponsored street kiosks and colossal corn statues. Built of cornhusks, cobs, and kernels, a statue of King Corn loomed over the street. News stories on the Atchison festival appeared in papers throughout the Midwest. The event even drew the attention of London’s Strand Magazine. Mrs. William Allen White, wife of another famed Kansas newspaper editor, wrote in her husband’s Emporia Gazette that “the love, the passion, the unselfishness, the fervor which the people of Oberammergau put into their Passion Play, the people of Atchison put into their Corn Carnival.”

Atchison’s Corn Carnival soon became a model for other Kansas towns, and with the bumper crops of 1899, dozens of similar crop carnivals were established. In Abilene, for example, leaders of the Commercial Club that year decided to send delegates to Atchison to bring home ideas that they could use for a carnival of their own. Corn costumes, corn dolls, parade floats, and music were among the features being considered, according to news reports. Abilene held its first Corn Carnival in October 1899, and more than ten thousand visitors came. The Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad shipped its giant King Corn statue to the city, and all the businesses decorated. An elected Corn Queen was enthroned at the town’s main intersection. Prizes were awarded for best costumes, floats, and corn-product displays.

Belleville, Kansas, in Republic County, also adopted the fad. In a competitive booster spirit, the editor of the local newspaper declared in August 1899, “Atchison has for the last few years had a corn carnival, but their corn crop doesn’t equal Republic County’s—so if they can have a successful corn carnival, why not we?” Belleville answered the challenge with a parade, dinner, concert, baby show, cakewalk, drill teams, races, and baseball games. Republic County continued to hold yearly carnivals through 1904.

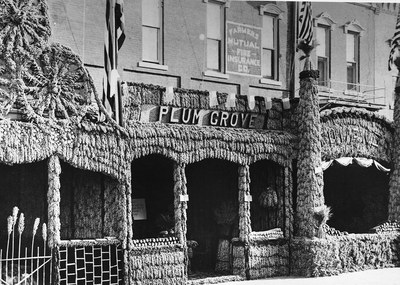

El Dorado, in Butler County, started its variation of the festival in 1911, with a Kafir Corn Carnival (the 1914 fair is pictured at the top of this section). A type of sorghum, Kafir corn had been introduced into the United States from South Africa in 1876. It came in white-, red-, and black-hulled variants, so it was especially useful for decorating. With the usual hoopla, local promoters sponsored essay contests on the advantages of Kafir corn. There was a Kafir Corn Queen and “something doing every minute,” according to newspaper reports: “There’s to be a big bunch of prominent men here to speak, bands and outdoor attractions of every kind, a lot of shows for the young folks to enjoy—and Kafir Corn everywhere.” Kiosks and porches improvisationally decorated with Kafir corn lined the streets. “It’s to be a regular carnival, with all the excitement and fun that mark such affairs and a lot of good, solid educative entertainment thrown in.”

Kansas was not the only place holding corn carnivals; they were all over the Midwest.

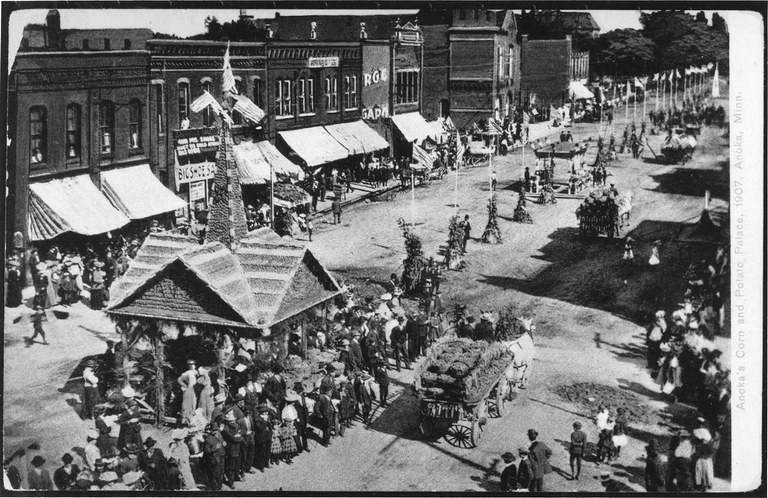

In 1899, anyone making a trip through Iowa, Nebraska, or Kansas would find “every other town preparing for a corn celebration,” declared a writer for Harper’s Weekly. At one such festival, he had heard an orator proclaim, “From the beginning of Indiana to the end of Nebraska, there is nothing but corn, cattle and contentment.” The size of the corn crop that year gave farm communities reason to celebrate. It was estimated that Kansas supplied nearly one-sixth of the nation’s corn in 1899, producing some 340 million bushels, or an average of about 41 bushels per acre. And it was not just Kansas that was having a good year. In Anoka, Minnesota, townspeople started holding a Corn and Potato Carnival in 1899, with a Ladies’ Flower Parade and street fair. In 1907, the town added a Potato Palace to celebrate its bumper crop (pictured at top of page). Some 70 bushels of potatoes covered the street pavilion. Red and white potatoes, yellow corn, red onions, asparagus grass, and orange pumpkins provided the color for what the local newspaper described as a “unique and tasteful design.”

For more great stories of state fairs of the past, check out Corn Palaces and Butter Queens by Pamela H. Simpson.

For more great stories of state fairs of the past, check out Corn Palaces and Butter Queens by Pamela H. Simpson.