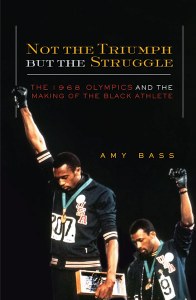

Not the Triumph but the Struggle

The 1968 Olympics and the Making of the Black Athlete

Amy Bass

In this far-reaching account, Amy Bass offers nothing less than a history of the black athlete. Beginning with the racial eugenics discussions of the early twentieth century and their continuing reverberations in popular perceptions of black physical abilities, Bass explores ongoing African American attempts to challenge these stereotypes. Although Tommie Smith and John Carlos were reviled by Olympic officials for their demonstration, Bass traces how their protest has come to be the defining image of the 1968 Games, with lingering effects in the sports world and on American popular culture generally.

In addition to being competition, entertainment, business, and shared experience, Sport has often been a stage where significant social issues were played out. In the twentieth century, those issues often pertained to human rights and race. Sometimes the dynamics of sports served to clarify those issues, sometimes to muddle them. Here, Amy Bass sorts through the events and perceptions linked to some of the biggest names and moments in sports history, and assesses their meaning beyond the playing field.

Bob Costas, NBC Sports

Jesse Owens. Muhammad Ali. Michael Jordan. Tiger Woods. All are iconic black athletes, as are Tommie Smith and John Carlos, the African American track and field medalists who raised black-gloved fists on the victory dais at the Mexico City Olympics and brought the roiling American racial politics of the late 1960s to a worldwide television audience. But few of those viewers fully realized what had led to this demonstration—events that included the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., uprisings in American cities, student protests around the world, the rise of the Black Power movement, and decolonization and apartheid in Africa.

In this far-reaching account, Amy Bass offers nothing less than a history of the black athlete. Beginning with the racial eugenics discussions of the early twentieth century and their continuing reverberations in popular perceptions of black physical abilities, Bass explores ongoing African American attempts to challenge these stereotypes. Although Tommie Smith and John Carlos were reviled by Olympic officials for their demonstration, Bass traces how their protest has come to be the defining image of the 1968 Games, with lingering effects in the sports world and on American popular culture generally.

$19.95 paper ISBN 978-0-8166-3945-8

462 pages, 5 7/8 x 9, 2004

Amy Bass is professor of history at the College of New Rochelle and is a member of the NBC research team covering the Olympic Games including Atlanta 1996, Sydney 2000, Salt Lake 2002, and Athens 2004.

In addition to being competition, entertainment, business, and shared experience, Sport has often been a stage where significant social issues were played out. In the twentieth century, those issues often pertained to human rights and race. Sometimes the dynamics of sports served to clarify those issues, sometimes to muddle them. Here, Amy Bass sorts through the events and perceptions linked to some of the biggest names and moments in sports history, and assesses their meaning beyond the playing field.

Bob Costas, NBC Sports

We all know the picture: John Carlos and Tommie Smith, fists raised in the Black Power salute, standing on the Olympic victory platform in Mexico City 1968. Perhaps more than any other symbol, it epitomizes the global reach of the black freedom movement, the politicization of the black athlete, as well as the crisis of authority in the West. Amy Bass's powerful and nuanced account of the Olympic Project for Human Rights gives us the story behind this picture—a story that will change our conception of the history of sport and racial politics.

Robin D. G. Kelley, author of Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination

Amy Bass gives her readers front row seats at the greatest contest of 20th century U.S. history: The African American struggle for equality. In her hands, a momentary gesture—the black power salute of medal winners Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the 1968 Olympics—opens a window onto the black struggle for dignity, political representation, and international solidarity with people of color. At a time when Americans want their heroes and their racial politics uncomplicated, Bass reminds us that neither ever is.

Glenda Gilmore, author of Gender and Jim Crow: Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina, 1896-1920

This is a crucial statement on race in today’s world, emphasizing the importance of collective struggles like the Black Power protest at the Mexico City Olympic Games in 1968. Amy Bass compels us to rethink all identities conceived in terms of traditional binaries like black and white, self and other, male and female in the increasingly transnational, commodified world of contemporary sport, a world that still uses the figure of the black athlete for its own exploitative ends.

Leslie Heywood, author of Pretty Good for a Girl: A Sports Memoir and Built to Win: The Rise of the Female Athlete as Cultural Icon

In her excellent new book, Not the Triumph but the Struggle, author Amy Bass uses the famous ‘black power’ podium salute by sprinters John Carlos and Tommie Smith as the centerpiece of her expansive examination of the black athlete in America.

Boston Globe

Absorbing and cogent, the book traces the ‘historical production of the black athlete,’ using the Olympic Project for Human Rights and the Black Power protests at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics as a simultaneously definitive and disruptive moment. Beautifully written, as well as appropriately complex and wide-ranging, the book examines the tangled relations among racism, global and national politics, commercialism, civil rights, national identity, labor and play, gender, ‘science’ (as this is recurrently used to ‘explain’ athletic prowess and performance), definitions of ‘professional’ and ‘amateur,’ television, and sports related industries (fashion, endorsements). As much as sports might appear to be a straight-ahead business, where the ‘best’ might be rightly rewarded, Bass deftly reveals the difficulties of maintaining a sense of self, collective consciousness, and political urgency—multimillion dollar contracts go a long way toward ‘erasing’ the ongoing effects of prejudice. ‘Victory can be defined in many ways,’ Bass concludes, ‘including by the struggle itself.’

Philadelphia City Paper

Amy Bass has made a significant contribution to the growing field of sport history by placing the 1968 Olympic protest within the larger context of the fight for civil rights during the 1960s. Bass has done an excellent job of examining this event and its portrayal in the media.

American Historical Review

There is much to ponder here in defining the Olympics as a place where both strong and weak countries seek to extend politics by athletic means. Bass tells her story well. Readers will find a nuanced rendering of IOC hypocrisy on questions of race, particularly as U.S. black-power advocates interacted with African athletes and debated boycotts aimed at ending apartheid.

International History Review

This ambitious study examines the attempt by Harry Edwards to spearhead a boycott of the 1968 Mexico City Olympics by African American athletes. Bass’s focus remains on the politicized nature of the Olympic Games and the emergence of ‘The Angry Black Athlete.’

Library Journal

When Muhammad Ali agreed to light the torch at the Olympic Games he was not just making another appearance, he was bestowing a blessing. These men and women are larger than their Games, and Bass’s book on Smith and Carlos helps us to understand why. Bass closes her excellent book with a meditation on the place of the modern black athlete in America.

Berkshire Eagle

Bass’s is a cultural analysis with a broad reach. We witness an essential moment in sports history, but we also learn about the construction of the black athlete as political figure, the lack of female leadership and participation within the OPHR movement, and the conversion of media image into intellectual property. A worthy book.

Aethlon

In this far-reaching examination, Bass—assistant professor of history at Pittsburgh State University and a research expert for the past three Olympics—explores the history of the black struggle and the events that led up to this unforgettable moment in time. Moreover, it's really a history of black athletes and their impact beyond the playing field.

Toronto Sun

Not the Triumph but the Struggle is as definitive a work as can be written on the post-World War II African American experience in sports. Her work is a stimulating, informative, and most interesting book to read. Scholars investigating the African American sporting experience have an intellectual debt to her for her pioneer work.

Journal of African American Men

It is rewarding to read Bass’s treatment and to be afforded the opportunity to relive and rethink the tumultuous sixties and a struggle for civil rights, empowerment, and human dignity that permeated even that holy sanctuary known as the Olympic Games.

Journal of American History

Contents

Note on Usage

Acknowledgments

Introduction: A Tiger in the Woods

1. The Race between Politics and Sport

2. What Is This “Black” in Black Athlete?

3. An Olympic Challenge: Preparing for the “Problem Games”

4. The Power of Protest and Boycott: The New York Athletic Club and the Question of the South African Springboks

5. Tribulations and the Trials: Black Consciousness and the Collective Body

6. “That’s My Flag”

7. Whose Broad Stripes and Bright Stars?

Notes

Index

UMP blog series - London 2012: A Woman's Place is on the Field

There are many reasons that I am a proud alum of Bates College – established by abolitionists, founded co-ed, sustainable campus, no Greek organizations – but reading about Keelin Godsey in the alumni magazine for the past several years has certainly been a highlight. In 2006, Bates reported on his second place finish in the shot put and his victory in the hammer throw at the NCAA Division III Women’s Outdoor Track and Field Championships. The meet marked his 15th and 16th All-America awards, making him the most decorated athlete in the college’s history.

Yes, I just used “his” and “him” to refer to an athlete competing in the women’s division: Godsey is a transgender athlete, and Bates reported it as straightforwardly as anyone could hope for.

The rigidity of gender perceptions in sport became reinforced with the debut of “femininity control” – gender verification testing – at the British Commonwealth Games in 1966. The testing eradicated any notion that a male/female binary could be complicated despite past cases such as Stella Walsh (Stanislawa Walasiewicz), who won gold in 1932 and silver in 1936 in the 100-meters and was later found to have male sex organs, and German high jumper Dora Ratjen, a hermaphrodite who was banned from competition after a fourth place finish in 1936. Gender verification made its Olympic debut in 1968 in the Winter Games in Grenoble; the IOC then made it mandatory for every woman competing in Mexico City. The sports press had a field day with the absurdity of witnessing women submit to having their mouths swabbed to prove their womanhood, particularly when it came to the athletes that the writers found to personify femininity. The AP wrote of U.S. swimmers Linda Gustavson and Pam Kruse, for example, that “no person in his right mind could have any question of their sex.”